Most people believe body camera implementation is a step in the right direction for police, although it will not end occurrences of excessive force.

Most people believe body camera implementation is a step in the right direction for police, although it will not end occurrences of excessive force.

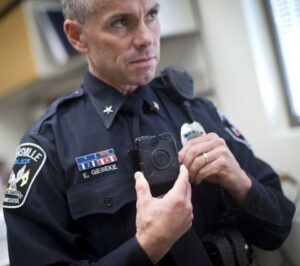

As a national debate erupts over police use of force, law enforcement agencies across the Upstate are taking a hard look at body cameras designed to record officer’s encounters and potentially shed light on instances of excessive force or even curtail it.

Many law enforcement agencies in the Upstate have at least a few body cameras, and others are weighing whether outfitting all officers with the recording devices is financially feasible or even necessary.

Some agencies, including those already storing the device recordings, are debating how long they should retain the videos and how their potential release under public records requests might impact the privacy rights of individuals — possibly children — captured on the videos.

And with deployment of the body cameras comes the recognition that it becomes painfully difficult to explain the absence of a video recording in cases when the technology malfunctions, the officer fails to turn it on or the camera simply doesn’t capture the critical moments.

“There’s a lot of unanswered questions when it comes to body cameras,” said Johnathan Bragg, spokesman for the Greenville City Police Department.

The questions don’t appear to be going away. Sens. Gerald Malloy and Marlon Kimpson pre-filed legislation earlier this month that would require all law enforcement officers in the state to wear body cameras that can record any and all contact with people while in the line of the duty.

“History has demonstrated that eyewitnesses are not always the most reliable form of evidence,” Malloy said. “It is time for South Carolina to invest in common-sense technology. This investment is critical to preserving the integrity of our system of justice.”

Liberty Police Chief Adam Gilstrap made just such an investment when his agency went all in on the idea of police officers wearing body cameras.

He liked the idea of additional accountability for his officers — and for the people they encounter. He liked knowing he could watch the video of an incident and remove all doubt as to what happened.

“I don’t have to go to someone and say, ‘Did you do this?’ And then worry about who’s telling the truth,” Gilstrap said.

He said he believes his small department has placed itself ahead of the curve.

Most believe body camera implementation is a step in the right direction, while acknowledging it likely won’t end instances of excessive force. Advocates of body cameras say statistics show that their use tends to reduce the number of confrontations with police and claims of mistreatment.

Police in Rialto, California, for example, reported a 60 percent reduction in use-of-force incidents following a pilot camera deployment program in 2012,

USA TODAY reported. There also was an 88 percent reduction in citizen complaints when compared with the prior year.

The State Law Enforcement Division has investigated about 40 officer-involved shootings this year, and 42 in 2013. The most reported in a single year is 44 in 2007 and 2012, said SLED spokesman Thom Berry.

The American Civil Liberties Union is generally supportive of police wearing body cameras, said Victoria Middleton, executive director of the ACLU of South Carolina.

“We think they’re a good thing, but they are not a panacea,” Middleton said. “They are not a cure all. As we saw with the choke hold death of Mr. (Eric) Garner in Staten Island, there was video. So it didn’t prevent problematic police practices.”

Retaining videos

The cost for more accountability comes with a price tag, and it’s not just the cameras.

Body cameras can range from as little as $100 to roughly $1,000, law enforcement agencies say. The Liberty Police Department, which has six patrol officers, chose $300 cameras made by Taser. The Greenville Police Department, using drug seizure funds, bought 40 body cameras at a cost of $865 each in November 2011, Bragg said.

Gilstrap, the Liberty police chief, said it would cost at least $2,000 a year, probably much more, for a company to store the department’s recordings on a server. The department has stored roughly 400 gigabytes of body camera footage, which doesn’t include in-car videos, he said.

Every morning, Gilstrap or another supervisor manually downloads the contents of the body cameras to its own system. That is not feasible for larger police departments.

Pickens County Sheriff Rick Clark said server space for body camera recordings can cost $10,000-$15,000 for a department his size that has 92 sworn officers.

Clark said he hasn’t established a policy for how long the body camera video recordings should be retained.

“It’ll just depend on how much storage we could buy and that’ll really determine our policy,” he said. “How much can we afford to hold?”

Gilstrap also hasn’t decided the appropriate amount of time to keep the videos, so everything that’s been recorded this year is still on the police computer server. The police department and city will use a joint server going forward, he said.

Some agencies lean on their policies regarding in-car cameras. The body-camera recordings for Greenville city police are stored on the same server as in-car cameras and kept for 45 days once downloaded by the officer, Bragg said.

The ACLU has stated that videos in which there is no reason to preserve evidence should be deleted relatively quickly, although not so soon as to prevent a citizen or attorney from filing a complaint. It suggests policies about retention should be posted on a police agency’s website so people know how long they have to request footage.

“And it’s important to have good policies in place to ensure that the video is not tampered with or abridged and that it’s stored properly to protect the privacy of everyone concerned — that includes the officer’s privacy,” Middleton said.

The Greenville Police Department, which has concerns about durability and cost of body cameras, does not have immediate plans to purchase more of them.

Of the 40 body cameras bought, 14 are inactive or out for repair, Bragg said. The body cameras were purchased for officers in patrol cars not equipped with in-car cameras. Now all of the cars have in-car cameras, and the body cameras are used mostly by special units like the SWAT team.

Senator Malloy said the bill is the start of a conversation, and funding should be a part of the discussion. But cost should not drive the discussion, he said.

“At the same time that they buy their Glock at $500, you can get our body camera, too, at $500,” he said. “That’s just simplifying it, but the real issue is: What’s it cost to outfit an officer? That’s where we’re going.”

“This society has changed,” he added. “And the society is: We’re going to be on camera.”

Clark, the Pickens County sheriff, said he keeps a body camera in his car to use when he goes out on calls. He likes the protection for himself and his officers.

He hopes the videos will give people a greater appreciation of what officers deal with on a daily basis. Making an arrest is not always easy, he said.

“Arresting people who don’t want to be arrested is not a nice procedure, and the law and court cases give us the ability to not only match their resistance or force they’re using on us, but to overcome that,” Clark said. “It may look bad, but there are certain things that have to be done on an arrest.”

Human error possible

Attorney Joshua Hawkins said he believes government employees should be subject to as much accountability as possible, including body cameras and in-car cameras. He worries that some body camera recordings won’t make it to court.

He said it is not unheard of for an attorney to request a video in a DUI case but be told it isn’t available.

“It’s lost or they don’t have it for some reason,” Hawkins said.

Tom Dunaway, an attorney in Anderson, has a lawsuit pending against the City of Anderson on behalf of Sharon McDowell’s family. She was shot and killed by police last December after police said she tried to ram police cars and run over officers, authorities said. Dunaway said officers shot at the woman, who was unarmed, 27 times and he contends the pursuit violated the police department’s chase policy.

Dunaway said a body camera was activated too late to show what happened and the video camera on the dashboard didn’t work.

“They’re denying they did anything wrong,” Dunaway said. “Had they had working equipment, it would have been easy to prove one way or the other.”

10th Circuit Solicitor Chrissy Adams declined to bring charges against police in the case, said Berry, the SLED spokesman.

Addressing body cameras in general without speaking to the Anderson case, Clark said it is possible an officer could get caught up in the moment and forget to turn on his camera when trying to help in a situation.

“When you do have cameras, everybody thinks that’s the panacea —100 percent of the time, the nice, clear movie-grade video will be there,” Clark said. “It’s going to make a great difference. But I don’t want people to expect 100 percent accuracy on everything because you’re dealing with humans and electronics. And a lot of times that’s not going to work.”

Although the implementation and use of body cameras will not be flawless, Gilstrap thinks body cameras are here to stay.

He said he remembers when there was some resistance to in-car cameras. Now they’re commonplace, especially among officers involved in traffic stops. Gilstrap said he believes the use of body cameras will only grow.

“In the upcoming years,” he said. “That’ll be as commonplace as handcuffs on your belt.”

If you have any questions regarding legal matters, please contact John Bateman, Attorney at Law, in Greenville, SC today!

Call

844.DUI.ALLY

Most people believe body camera implementation is a step in the right direction for police, although it will not end occurrences of excessive force.

Most people believe body camera implementation is a step in the right direction for police, although it will not end occurrences of excessive force.